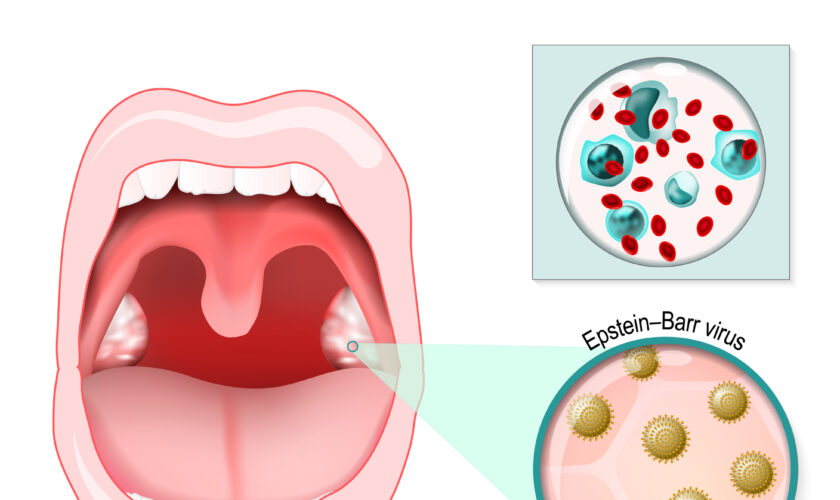

Infectious mononucleosis, or mono, refers to a group of symptoms usually caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). It typically occurs in teenagers, but you can get it at any age. The virus is spread through saliva, which is why some people call it “the kissing disease.”

Many people develop EBV infections as children after age 1. In very young children, symptoms are usually nonexistent or so mild that they aren’t recognized as mono. Once you have an EBV infection, you aren’t likely to get another one. Any child who gets EBV will probably be immune to mono for the rest of their life.

People with mono often have a high fever, swollen lymph glands, and a sore throat. Most cases of mono are mild and resolve easily with minimal treatment. The infection is typically not serious and usually goes away on its own in one to two months.

The incubation period of the virus is the time between when you contract the infection and when you start to have symptoms. It lasts four to six weeks. The signs and symptoms of mono typically last for one to two months.

The symptoms may include:

Occasionally, your spleen or liver may also swell, but mononucleosis is rarely ever fatal.

Mono is hard to distinguish from other common viruses such as the flu. If your symptoms don’t improve after one or two weeks of home treatment such as resting, getting enough fluids, and eating healthy foods, see your doctor.

Mononucleosis is caused by the EBV. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), EBV is a member of the herpes virus family and is one of the most common viruses to infect humans around the world.

The virus is spread through direct contact with saliva from the mouth of an infected person or other bodily fluids such as blood. It’s also spread through sexual contact and organ transplantation. You can be exposed to the virus by a cough or sneeze, by kissing, or by sharing food or drinks with someone who has mono. It usually takes four to eight weeks for symptoms to develop after you’re infected.

In adolescents and adults, the infection causes noticeable symptoms in 35 to 50 percent of cases. In children, the virus typically causes no symptoms, and the infection often goes unrecognized.

The following groups have a higher risk for getting mono:

Anyone who regularly comes into close contact with large numbers of people is at an increased risk for mono. This is why high school and college students frequently become infected.

Because other, more serious viruses such as hepatitis A can cause symptoms similar to mono, your doctor will work to rule out these possibilities.

Once you visit your doctor, they’ll normally ask how long you’ve had symptoms. If you’re between age 15 and 25, your doctor might also ask if you’ve been in contact with any individuals who have mono. Age is one of the main factors for diagnosing mono along with the most common symptoms: fever, sore throat, and swollen glands.

Your doctor will take your temperature and check the glands in your neck, armpits, and groin. Your doctor might also check the upper left part of your stomach to determine if your spleen is enlarged.

Sometimes your doctor will request a complete blood count. This blood test will help your doctor determine how severe your illness is by looking at your levels of various blood cells. For example, a high lymphocyte count often indicates an infection such as mono.

A mono infection typically causes your body to produce more white blood cells as it tries to defend itself. A high white blood cell count can’t confirm an infection with EBV, but the result suggests that it’s a strong possibility.

Lab tests are the second part of a doctor’s diagnosis. One of the most reliable ways to diagnose mononucleosis is the monospot test (or heterophile test). This blood test looks for antibodies —these are proteins your immune system produces in response to harmful elements. However, it doesn’t look for EBV antibodies. Instead, the monospot test determines your levels of another group of antibodies your body is likely to produce when you’re infected with EBV. These are called heterophile antibodies.

The results of this test are the most consistent when it’s done between two and four weeks after symptoms of mono appear. At this point, you would have sufficient amounts of heterophile antibodies to trigger a reliable positive response.

This test isn’t always accurate, but it’s easy to do, and results are usually available within one hour or less.

If your monospot test comes back negative, your doctor might order an EBV antibody test. This blood test looks for EBV-specific antibodies. This test can detect mono as early as the first week you have symptoms, but it takes longer to get the results.

There’s no specific treatment for infectious mononucleosis. However, your doctor may prescribe a corticosteroid medication to reduce throat and tonsil swelling. The symptoms usually resolve on their own in one to two months.

Treatment is aimed at easing your symptoms. This includes using over-the-counter (OTC)medicines to reduce fever and techniques to calm a sore throat, such as gargling salt water. Other home treatments that may ease symptoms include:

Contact your doctor if your symptoms get worse or if you have intense abdominal pain.

Mono is typically not serious. In some cases, people who have mono get secondary infections such as strep throat, sinus infections, or tonsillitis. In rare cases, some people may develop the following complications:

You should wait at least one month before doing any vigorous activities, lifting heavy objects, or playing contact sports to avoid rupturing your spleen, which may be swollen from the infection. Talk to your doctor about when you can return to your normal activities. A ruptured spleen in people who have mono is rare, but it is a life-threatening emergency. Call your doctor immediately if you have mono and experience a sharp, sudden pain in the upper left part of your abdomen.

Hepatitis (liver inflammation) or jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) may occasionally occur in people who have mono.

According to the Mayo Clinic, mono can also cause some of these extremely rare complications:

The symptoms of mono seldom last for more than four months. The majority of people who have mono recover within two to four weeks.

An illness called chronic EBV infection can occur if symptoms last for more than six months. EBV will remain dormant in your blood cells for the rest of your life, and it can occasionally reactivate without symptoms. It’s possible to spread the virus to others through contact with your saliva during this time.

EBV also establishes a lifelong, inactive infection in your body’s immune system cells. In some very rare cases, people who carry the virus develop either Burkitt’s lymphoma or nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which are both rare cancers. EBV appears to play a role in the development of these cancers. However, EBV is probably not the only cause.

Mono is almost impossible to prevent. This is because healthy people who have been infected with EBV in the past can carry and spread the infection periodically for the rest of their lives. Almost all adults have been infected with EBV by age 35 and have built up antibodies to fight the infection. People normally get mono only once in their lives.