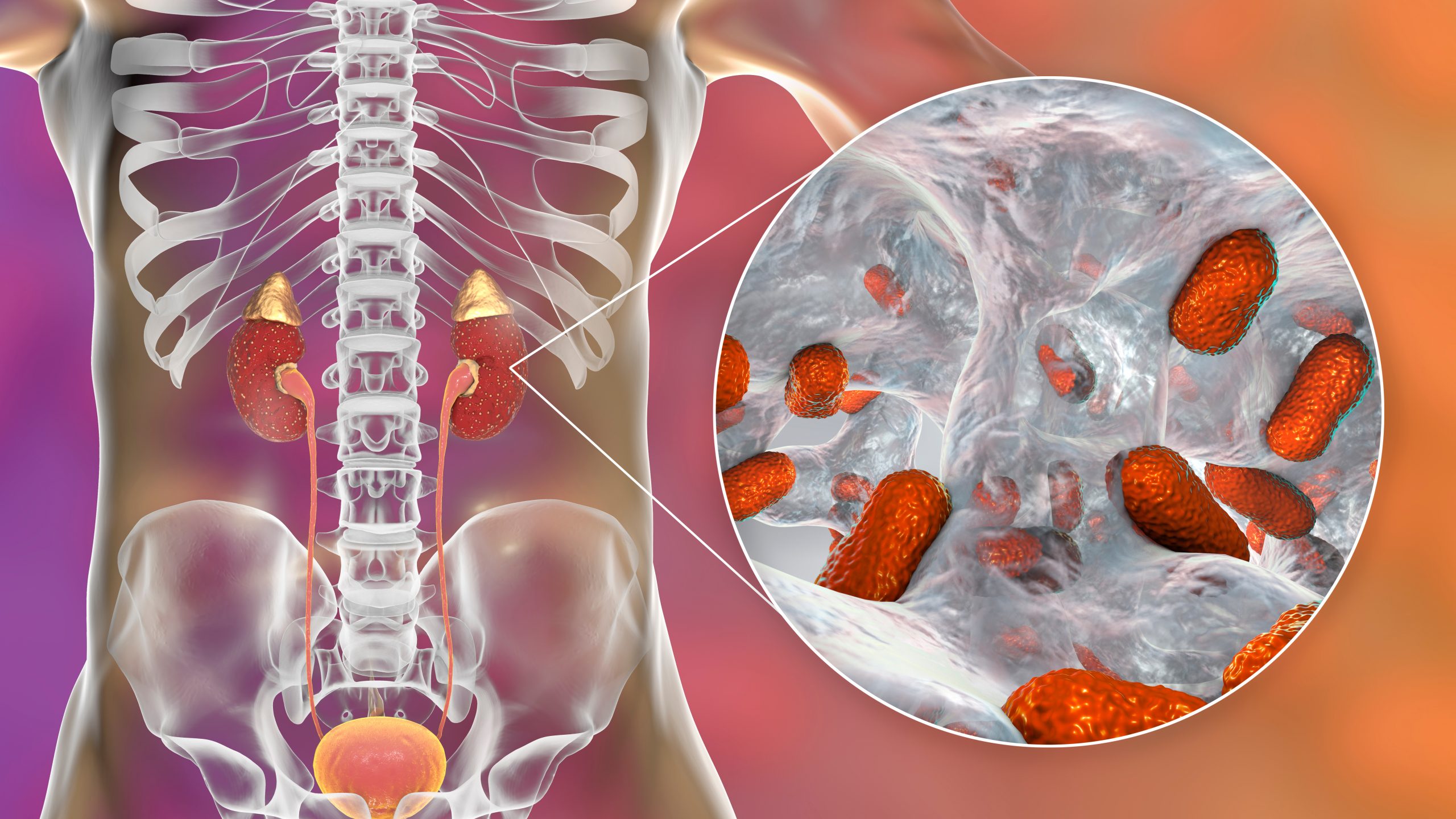

Acute pyelonephritis is a potentially organ- and/or life-threatening infection that often leads to renal scarring. Acute pyelonephritis results from bacterial invasion of the renal parenchyma. Bacteria usually reach the kidney by ascending from the lower urinary tract. Bacteria may also reach the kidney via the bloodstream. Timely diagnosis and management of acute pyelonephritis has a significant impact on patient outcomes.

The classic presentation in patients with acute pyelonephritis is as follows:

Fever - This is not always present, but when it is, it is not unusual for the temperature to exceed 103°F (39.4°C)

Costovertebral angle pain - Pain may be mild, moderate, or severe; flank or costovertebral angle tenderness is most commonly unilateral over the involved kidney, although bilateral discomfort may be present

Nausea and/or vomiting - These vary in frequency and intensity, from absent to severe; anorexia is common in patients with acute pyelonephritis

Gross hematuria (hemorrhagic cystitis), unusual in males with pyelonephritis, occurs in 30-40% of females, most often young women, with the disorder.

Symptoms of acute pyelonephritis usually develop over hours or over the course of a day but may not occur at the same time. If the patient is male, elderly, or a child or has had symptoms for more than 7 days, the infection should be considered complicated until proven otherwise.

The classic manifestations of acute pyelonephritis observed in adults are often absent in children, particularly neonates and infants. In children aged 2 years or younger, the most common signs and symptoms of urinary tract infection (UTI) are as follows:

Failure to thrive

Feeding difficulty

Fever

Vomiting

Elderly patients may present with typical manifestations of pyelonephritis, or they may experience the following:

Fever

Mental status change

Decompensation in another organ system

In the outpatient setting, pyelonephritis is usually suggested by a patient’s history and physical examination and supported by urinalysis results. Urine specimens can be collected through the following methods:

Clean catch

Urethral catheterization

Suprapubic needle aspiration

Urinalysis can include the following:

Dipstick leukocyte esterase test (LET) - Helps to screen for pyuria

Nitrite production test (NPT) - To screen for bacteriuria

Examination for hematuria (gross and microscopic) and proteinuria

Urine culture is indicated in any patient with pyelonephritis, whether treated in an inpatient or outpatient setting, because of the possibility of antibiotic resistance.

Imaging studies that may be used in assessing acute pyelonephritis include the following:

Computed tomography (CT) scanning - To identify alterations in renal parenchymal perfusion; alterations in contrast excretion, perinephric fluid, and nonrenal disease; gas-forming infections; hemorrhage; inflammatory masses; and obstruction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – To detect renal infection or masses and urinary obstruction, as well as to evaluate renal vasculature

Ultrasonography - To screen for urinary obstruction in children admitted for febrile illnesses and to examine patients for renal abscesses, acute focal bacterial nephritis, and stones (in xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis)

Scintigraphy - To detect focal renal abnormalities

Antibiotic therapy is essential in the treatment of acute pyelonephritis and prevents progression of the infection. Urine culture and sensitivity testing should always be performed, and empirical therapy should be tailored to the infecting uropathogen. [3]

Patients presenting with complicated pyelonephritis should be managed as inpatients and treated empirically with broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics.

Outpatient care

Outpatient treatment is appropriate for patients who have an uncomplicated infection that does not warrant hospitalization. Patients presenting with acute pyelonephritis can be treated with a single dose of a parenteral antibiotic followed by oral therapy, provided that they are monitored within the first 48 hours.

Inpatient care

Inpatient care includes the following:

Supportive care

Monitoring of urine and blood culture results

Monitoring of comorbid conditions for deterioration

Maintenance of hydration status with IV fluids until hydration can be maintained with oral intake

IV antibiotics until defervescence and significant symptomatic improvement occur; convert to an oral regimen tailored to urine or blood culture results

Surgery

In addition to antibiotics, surgery may be necessary to treat the following manifestations of acute pyelonephritis:

Renal cortical abscess (renal carbuncle): Surgical drainage (if patients do not respond to antibiotic therapy); other surgical options are enucleation of the carbuncle and nephrectomy

Renal corticomedullary abscess: Incision and drainage, nephrectomy

Perinephric abscess: Drainage, nephrectomy

Calculi-related urinary tract infection (UTI): Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) or endoscopic, percutaneous, or open surgery

Renal papillary necrosis: CT scan ̶ guided drainage or surgical drainage with debridement

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: Nephrectomy

Most people affected by acute pyelonephritis are successfully treated with antibiotics and do not need to be hospitalised. However, in cases of very severe and/or complicated infections, hospitalisation may be safest in order to monitor the infection consistently and to control its spread most effectively. Hospitalisation can be avoided if treatment is sought early on in the course of the infection.

Bed rest, painkillers and hydration are the cornerstones of home treatment for acute pyelonephritis. Staying well hydrated helps to heal the kidneys and flush out the pathogens. However, over-hydration is counterproductive and should be avoided. Painkillers such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen can be taken orally to manage pain.

The most common form of treatment for acute pyelonephritis is antibiotics. In some cases, the infection may involve drug-resistant strains of bacteria or the wrong dosage or wrong drug is prescribed. In such instances, antibiotics will not work and the risk of developing complications increases. However, antibiotics generally do work.

Some of the oral antibiotics most commonly prescribed are:

Oral beta-lactam antibiotics, trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole are generally not helpful. There is considerable resistance to fluoroquinolones among E. coli bacteria, and so treatment with such antibiotics may not be efficacious.

In cases of severe or complicated infection, hospitalisation is advised. Much like home treatment, inpatient treatment involves antibiotics, painkillers and monitoring for approximately five days and possibly longer, depending on local practice. In some cases, surgery may be required to deal with underlying conditions causing complications, such as enlarged prostate or kidney stones. Also, in severe cases, surgery may be necessary to drain pus away from the kidneys. Antibiotics may be delivered intravenously into a vein in the arm, via a drip, including:

There are certain circumstances in which a patient should be hospitalised. Sepsis and septic shock are serious complications of acute pyelonephritis, and if any signs of sepsis are present, the patient should be hospitalised without delay. Other circumstances suggesting that hospitalisation would be wise include: